The Fiction of Place and

the Real of Narrative

“And so, what we call art exists in order to give back the sensation of life, in order to make us feel things, in order to make the stone stony. The goal of art is to create the sensation of seeing, and not merely recognizing, things; the device of art is the ‘ostranenie’ of things and the complication of the form, which increases the duration and complexity of perception, as the process of perception is its own end in art and must be prolonged.” [Viktor Shklovsky. Art as Device. In: Alexandra Berlina (ed.). Viktor Shklovsky A Reader. New York, 2017. p.80]

With this conference, we aim to present contemporary positions in architectural discourse and practice that have offered complex and already influential descriptions of contextual relations. It is our hope that we can gain a more refined understanding of the diverse contexts that shape architectural projects in relation to the demands of place as well as of discourse. We want to stress the importance of narratives and related design techniques that help to establish critical dialogues between, building, place, and discipline.

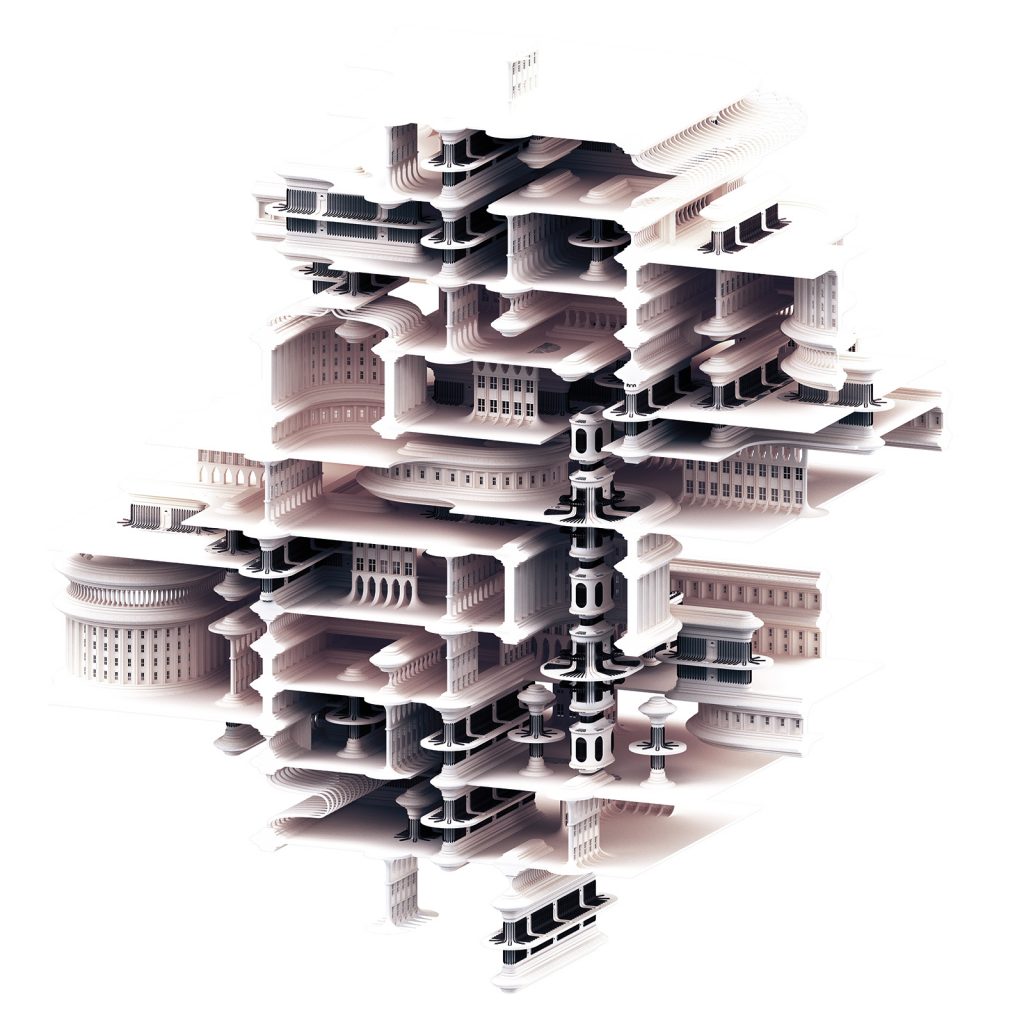

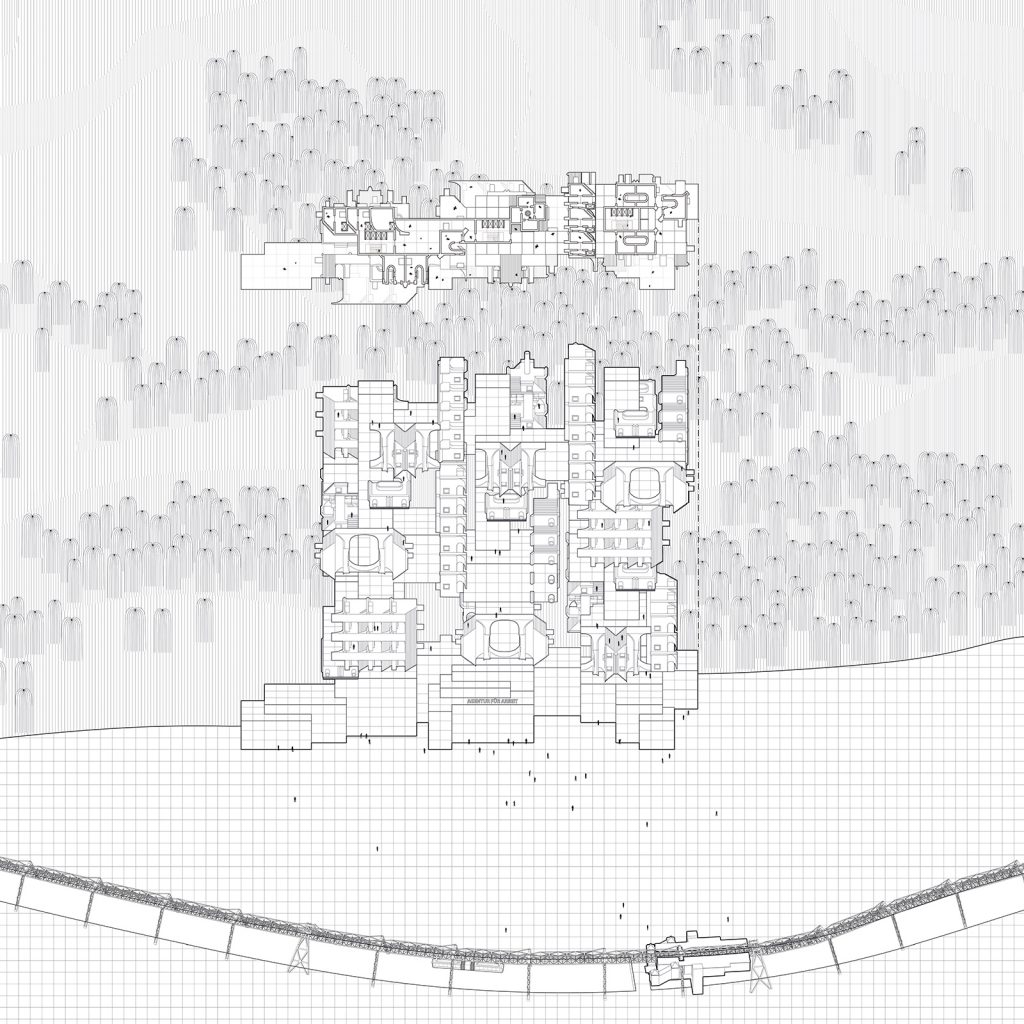

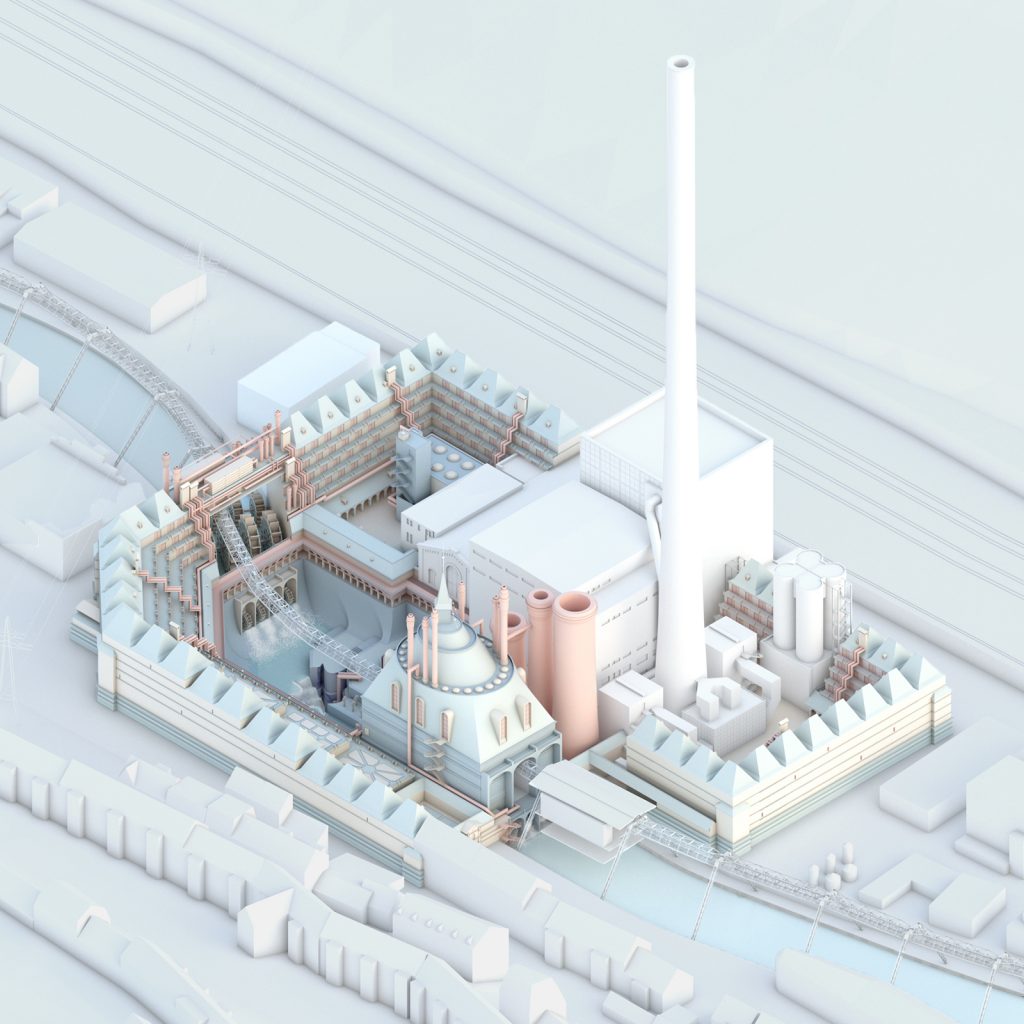

The conference begins on March, 26th, with a soft opening of an exhibition that showcases a recent research-project conducted at the ‘Chair for Techniques of Representation and Design’ of Bergische Universität Wuppertal: The Weird Landmark is made of five fictional architectural interventions that are located along Wuppertal’s Schwebebahn. On March, 27th, six internationally renowned lecturers will explore the intricate relationships of architectural projects and their diverse contexts in theory and practice.

Wuppertal

The city of Wuppertal is a remarkable place – especially regarding the understanding of context in contemporary architectural discourse. Like many German cities, Wuppertal has undergone significant transformations due to its important role as a hot spot of early industrialization in Germany, its destruction during the bombing raids of Second World War, its reconstruction as a car-friendly city since the 1950s, as well as through economic decline and structural change since then. Today, the city presents itself as a collage of, scales, styles, intentions, and ideologies that have shaped both, very coherent urban quarters, as well as often-extreme collisions or discontinuities among them. Wuppertal is a heterogeneous physical reality as it is also an aggregation of narratives, such as in Wim Wenders’ Movie pina that displays Wuppertal as both, background and protagonist. In this, Wuppertal is special, yet not different from many other cities.

However, with the construction of a suspended railway (Schwebebahn) at the beginning of 20th Century, the citizens of Wuppertal erected a cinematographic apparatus that, today, connects the city’s polycentric layout. Its lattice-structure depicts the inventiveness and bravery of early modernization and it has made the Schwebebahn the most prominent landmark of Wuppertal. Like most means of transportation, it is an every-day object; a routine that positions commuters in an “unconscious-automatic domain”[1]. But, because of the way it visualizes the city from an elevated position that continuously moves, it also transcends this routine. The Schwebebahn creates a “sensation of seeing, and not merely recognizing” (Shklovsky) the incongruent contexts of the city. As a visual device, that exceeds the mere necessities of transportation, the Schwebebahn allows to experience the various, versions, realities, and fictions, of Wuppertal.

[1] “Considering the laws of perception, we see that routine actions become automatic. All our skills retreat into the unconscious-automatic domain…” In: Shklovsky, p.79

Context as Device

From today’s point of view, the notion of context appears to be one of the most used and seemingly obvious, but at the same time also indifferent and somewhat mysterious, cornerstones of architectural projects.

Introduced in the 1960s to architectural discourse as the “first substantial critique of modernist practice”[2], the term describes the relation of a built project to its “surrounding pre-existences” (“preesistenze ambientali”) or its place. From such a point of view context contains an even moral dimension that considers the prevention “of a misfit between the form and the context” (Christopher Alexander) or the revelation of “the essence of the surrounding context” (Vittorio Gregotti) desirable. Such an approach often relies on the approximation of a project to the existing conventions of a place regarding, gestalt, typology, or materialization. Then, this so-called “place form” originates from the similarity or even sameness of object and background, and is considered correct, or true. Such an understanding of context is widely accepted up until today.

[2] Adrian Forty. Words and Buildings. A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. London, 2000. p.132

Despite the notion of place, there are other concepts of context. The introduction of drawing techniques or “notation” as an “allographic way of building”[3] during the European Renaissance means the separation between the design and materialization of an architectural project. With those techniques at hand, architects can open the process of design (or “lineamenti”) towards influences outside a specific site or local methods of materialization. In this sense, the conception of an architectural project does not rely solely on the conventions of a specific place as the main reference. Other themes, shared through drawing or writing, gain influence and establish contexts beyond the specificity of place. Additionally, instead of learning “the business by working, as articled pupils or apprentices, in the workplace of practicing architects”[4], architectural design is taught, now bound to a disciplinary discourse or context with a focus on design itself.

[3] Mario Carpo. The Alphabet and the Algorithm.

Cambridge, 2011. p.22

[4] Forty, p.137

The invention of photography during the 19th Century fosters this development. Printed imagery had already been used to propose influential projects outside the realm of built reality. Now, new methods of technical reproduction pave the way for both, new design techniques, such as montages (like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Concert Hall Project from 1942) but also a greater and increasingly global audience. The image of a building or a design-vision responds to, or establishes a context beyond place. This is especially true for an architecture that claims Avant-Garde-positions. Here, place performs either as an image of a tradition to overcome (like the ornamented facades of a Wilhelminian Berlin that darkly frame Mies’ Friedrichstraße Skyscraper, 1921), or as a decidedly unspecific background (like the surrounding landscape of Mies’ Farnsworth House, 1950/51). Both cases reduce place to a mere stage to exhibit the novelty and universalism of an architecture-to-come.

However, behind such expressed novelty that presented itself with “the elementariness of de Stijl, the rappel à l’ordre of Le Corbusier, and the Neue Sachlichkeit in Germany and Switzerland”[5], often lies a deep understanding of architectural tradition and locality, too. Accordingly, Colin Rowe highlighted the roots of Corbusier’s villas with their Palladian background, while Alan Colquhoun described the derivation of Le Corbusier’s cube-shaped white walls from Mediterranean vernacular.

[5] Alan Colquhoun. The Concept of Regionalism. In: Vincent B. Canizaro (ed.). Architectural Regionalism. Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition. New York, 2007, p.147

Contextual relations, whether bound to place or discourse, are, too, a work of fiction and narrative that appears a bit more intricate than the often claimed dichotomy of, place and discourse, fit and deliberate misfit, or continuity and novelty.

Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan might be a good example here. Parallel to the completion of the actual building in 1949, Johnson published a “critical essay” in Architectural Review (1950), in which he described the relevant references for his project. Despite the house’s modernist appearance, he exemplifies the embedding of the house by means of various traces to architectural or local tradition: “The genius of the Glass House obtains from the fact that, although it derives its style from modernism, the discrete, ordered space it engenders belongs more to classical architecture.”[6]

[6] Jeffrey Kipnis. Throwing Stones – The Incidental Effects of a Glass House. In: David Whitney, Jeffrey Kipnis (ed.). Philip Johnson. The Glass House. New York, 1993. p.xvi

This resolute display of disciplinary continuity is a major difference to Mies’ Farnsworth House. Where Mies’ house floats above ground, Johnson’s formulates brick-foundations. Where Mies “redeploys all of the components of a neoclassical house in order to achieve the characteristic flowing, continuous space of canonic modern architecture”, Johnson transforms elements and figures mined from classical, local, or even vernacular architecture like the handrail-like window-frame that resembles the handrail of American porches. In this way, the house is a strange object on many levels, both bound to and critical towards place and discipline.

This attempt to create resistance against both, the deliberate presentation of novelty aiming at a global audience, as well as the unquestioned use of patterns found at a specific place [7], is meant to be the role model for this conference.

[7] “The second meaning Tzonis and Lefaivre give to the word ‘critical’ is to create resistance against the merely nostalgic return of the past by removing regional elements from their natural contexts so as to defamiliarize them and create an effect of estrangement. This seems to be based on the Russian formalist strategy of ‘making strange’”, In: Colquhoun, p.151

The effects of estrangement that result from a critical reading of place-specific phenomena and their transformation with contemporary techniques of design and representation “are oriented less toward the disappearance of the real than toward the pragmatics of trust”[8].

[8] Carrie Lambert-Beatty: Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility. October Magazine, Ltd. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2009, URL: www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/octo.2009.129.1.51 – Web. 27.4.2017

Ideally the architectural object serves as a critical counterpart to its context, whereby the introduced shift might help to see the seemingly familiar in different ways resulting in „an allure, a strangeness that draws one in“ [9].

[9] Michael Young. Estrangement & Objects. In: Michael Young & Kutan Ayata. The Estranged Object. Chicago, 2014. p.29